At a young age I discovered a magical device in the form of a plastic toy camera.

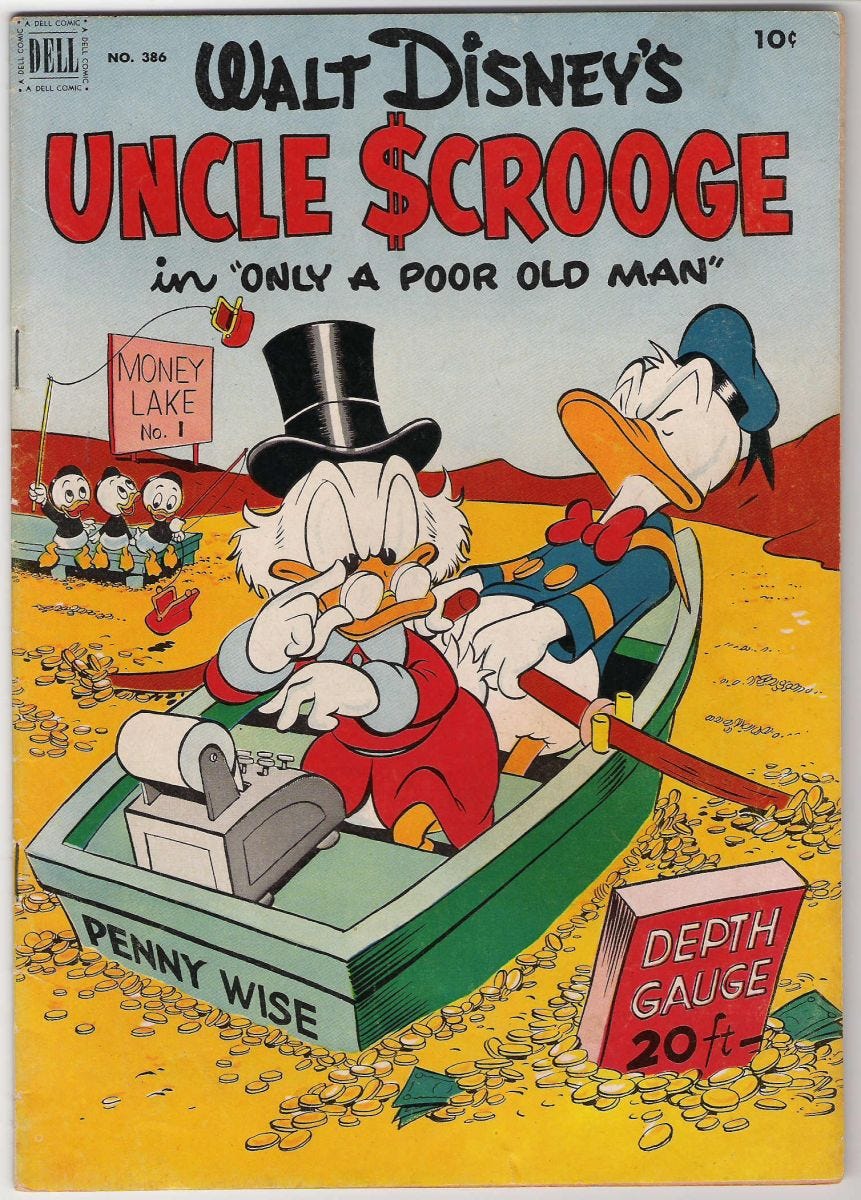

Within the back pages of Dell Comics, among ads for sea monkeys and x-ray specs, images of a small camera grabbed my attention.

After cutting out the coupon and adding the required payment, I wrote down the address and sent off the order. A few weeks later the camera arrived.

Printed instructions taught me how to load film, stand with the sun behind me and click away. My first attempts into the mysterious world of photography included my dog, Scout, the backyard playhouse and maybe some cherry trees.

Film development was handled through drug stores at that time, and the closest one was Hank’s Pharmacy about two blocks away. After a week, the negatives and prints arrived. Only two images out of the 12 negative roll survived - one of the playhouse and the other a clothesline. The rest of the negatives represented a total failure in my premier endeavor into the art of photography. That included unexposed images, light leaks and horribly overexposed negatives. The lesson was obvious. Photography requires an ability to read light and an attention span longer than that of a ground squirrel.

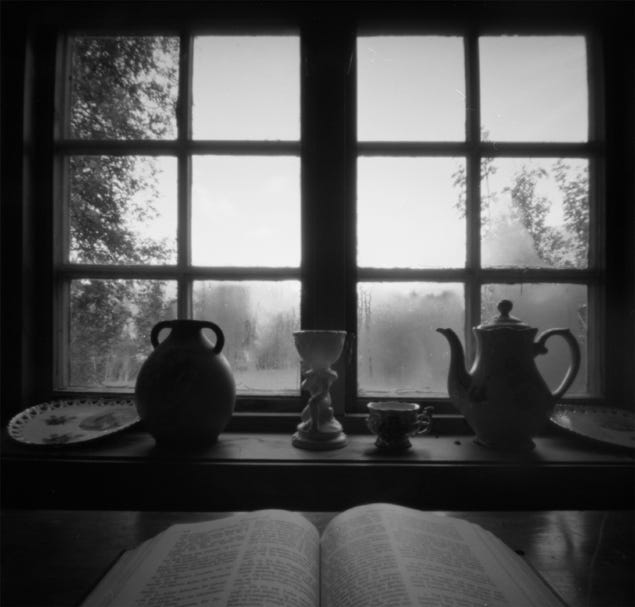

Undeterred, I bought a second roll of Kodak, Plus X black and white film and followed some simple rules – use open shade for my light, do not shake the camera and keep the subject still. That second roll captured time and space – sort of a journey into a mystical world -in this case a photo of a boat my brother was building and a neighbor’s fence.

Definitely not the face of God, but an intriguing experience. Black and white prints last about 100 years, and my images captured a moment about 65 years ago.

The magical device employed an aperture, a shutter, a tiny, light tight device and chemically coated film. In this case a tiny hole or aperture rested on the plastic lens. The light hit the film by a shutter spring firing off by about 1/60 of a second. The film was covered with silver halides that reacted to light and made a reversed image. Hence the name: negative.

Thanks to William Henry Fox the negative was invented in the 1830’s allowing photographers to reproduce the same image numerous times. As I learned in childhood, the process was a bit complicated and required a large dose of mindfulness.

Today our smart phones use a digital sensor, known as a CCD or CMOS chip, to capture and record an image. These sensors convert light into electrical signals, which are then processed and stored.

Ok, enough of the technical stuff. The point is that our smart phones have become ubiquitous. It's estimated that billions of photos are taken on smartphones every single day.

For this photo buff, I agree with B.B. King, “The thrill is gone”. Phone photography acts more as documentation than a visual aesthetic endeavor. In fact, phones become obstacles to the experience in front of us. Think about charming, spontaneous events like a flash mob and how many observers bring out their phones to make the event a reality.

The magic of photography involves the mechanical capture of a specific time and vision. If we think of our lives as a finite series of moments, photography is the craft that freezes those instances for reflection and fascination. The daily, billions of images through phone photography record moments in our lives but take on a certain passivity or distance just by their casualness.

I had these thoughts while introducing Sierra College students to the fun of pinhole photography. Thanks to a concept of camera obscura, we applied the principles of light traveling in straight lines and becoming a focal point by entering a tiny aperture and projecting light on photographic film or paper.

The technology savvy students from modern suburbia went retro., The constructed cardboard boxes, created light-tight chambers and experimented with exposure time in a variety of lighting situations. In the darkroom the intrigue continued as they created 4 x 6 negatives and made contact prints, again experimenting with light intensity and exposure time. The results were fascinating.

Again, using the principles of the Camera Obscura, or “dark chamber” dating back to the Renaissance, the students employed the same concepts. Camera obscuras work by allowing light to pass through a small opening, like a tiny aperture or lens, and onto a screen or wall inside a darkened space.

A pinhole camera works because of that small hole which is the aperture. Light from the sun enters the pinhole, it gets focused, and then it is projected on the other side of the camera. In the darkroom the photographer develops the negative after lots of test strips, then makes a “contact print” sandwiching the negative on top of fresh photographic paper.

Ok, it is not nuclear fusion, but the process takes meticulous calculations and the ability to read light. The students produced images in a variety of lighting situations and in the process developed an eye for visual contrast, light and shadow.

Most importantly, the process took a sort of mindfulness. They thrived while engaged in a wonderous process of stopping time.

Not a bad way to introduce people to the wonders of photography. They put their smart phones down and became fully engaged with their magical boxes.

I should mention that Rick has had gallery shows in Northern California and published photos in books. His classes in high school and college were memorable.

Thanks for the fun nostalgic trip. I ended up giving all my film cameras and associated equipment to the Colfax High photo dept a few years ago. I've gone full cellphone photography. It's just so convenient. But I miss holding photos in my hands.